Elizabeth Lindsay was born in 1760 in Falling Springs (now Chambersburg), Pennsylvania, to William and Margaret Ewing Lindsay. The Lindsays were a wealthy family from Philadelphia. Elizabeth was well-educated and skilled in the social graces.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: Read a description of the Lindsay home!

A nearby neighbor, Robert Patterson, from Cumberland (now Bedford) County, visited the Lindsays often, and became acquainted with Elizabeth and her brothers, William, James, Henry, Joseph, and Arthur, and sister, Jane.

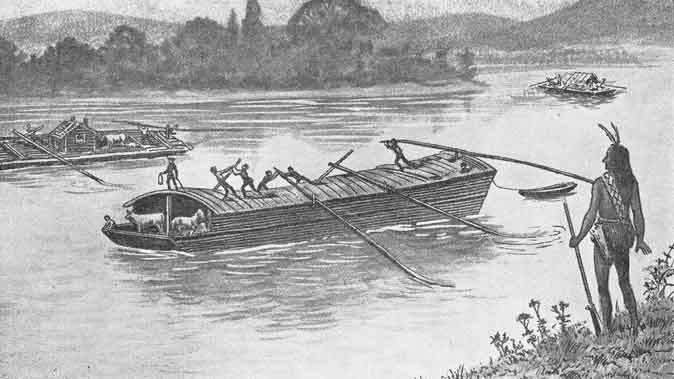

Following the westward migration of colonial Americans over the Appalachian Mountains and down the Ohio River, Robert moved to the Kentucky Territory in summer 1775 to stake land claims. In the fall, William and Joseph Lindsay also left for Kentucky to stake land claims.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: How did settlers claim land?

At the beginning of the war, Robert, and William and Joseph Lindsay, joined the militia and fought many battles with the Native Americans in the Ohio Country as the British incited most of the tribes to fight against the Americans. The Native Americans frequently staged raids into the Kentucky Territory. The British promised the Native Americans that they would retain their lands in exchange for helping them.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: What tribes in Ohio fought for the British?

While recovering from wounds after a Native-American attack in October 1776, Robert spent several months at Fort Pitt (present day Pittsburgh) before returning home to recover.

In spring 1777, Robert visited relatives and neighbors as he recovered, including the Lindsay family. He and Elizabeth Lindsay became engaged.

Robert and Elizabeth were separated for three years because of the war. Elizabeth sent a letter reminding Robert of their engagement and he took a leave of absence. On March 29, 1780, Robert and Elizabeth were married in the Lindsay home in Falling Springs.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: Read about the wedding!

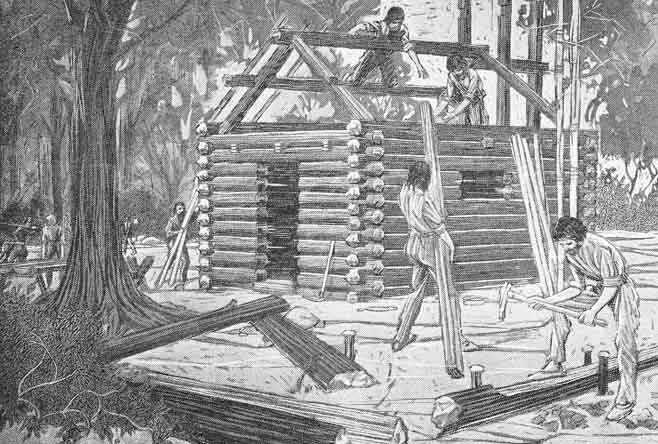

Robert and Elizabeth then made the long, hazardous trip to his primitive, one-room cabin in the Kentucky wilderness. This was very different from the large, elegant home in which Elizabeth was raised.

Elizabeth later recounted, "The feeling of hesitation passed quickly and forever when the women of the Fort came in to welcome me and began showing beautiful furs and pelts to adorn our floors, walls and bed. The kettles, oven and other utensils my husband provided for my coming were the best to be had on the border..." (From the Henry L. Brown Papers, Conover, 1902, p. 199).

As a new wife in the wilderness, Elizabeth learned how to milk cows, churn milk into butter, dye petticoats with walnut hulls, pound corn in a mortar for Johnny-cake, besides cooking, cleaning, and washing clothes.

Because Native-American attacks were common, women often had to remain in the stockade while men worked in the fields. Elizabeth realized how precarious life on the frontier was when the bodies of two settlers killed by Native Americans were carried into Lexington shortly after her arrival.

As Elizabeth learned how to be a settler's wife, Robert continued to serve in the militia in support of America.

On August 15, 1782, British Rangers, and Wyandot and other Native Americans from the Great Lakes region, laid siege to Bryant's Station in the Kentucky Territory. The next day, Robert Patterson led the Lexington militia to Bryant's Station and repelled the siege.

Within a few days, militiamen from all over the Kentucky Territory, including Daniel Boone, arrived at Bryant's Station. A decision was made to pursue the British and Native Americans with a battle erupting near the Licking River on August 19. Seventy-two militiamen, including Elizabeth's brother, Joseph, were killed. Robert barely escaped capture.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: Read about Elizabeth's thoughts on the Battle of Blue Licks!

Although the Revolutionary War ended in 1783 with the Treaty of Paris, the British maintained forts in Canada near the Great Lakes. The British supported the various Native-American tribes who lived there and promised to support their efforts to curb the influx of white settlers.

British support of the natives led to conflict with the westward-moving white families making land claims. As a result, Robert engaged in military campaigns to the Ohio Country in 1782, 1786, and 1791 to prevent raids into Kentucky.

During this time, Robert and Elizabeth had 11 children, nine of whom lived to adulthood. This was a remarkable achievement as nearly 50% of all children at this time died before 5 years of age.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: Who were the Patterson children?

Robert lost his Kentucky property due to a bad decision to secure a loan for a friend in 1799. With nine children to support and plenty of available, inexpensive land in the Ohio Country, he moved to the Miami Valley.

Robert's military campaigns there impressed him with the fertility of the land between the two Miami Rivers. In 1803, he purchased Daniel Cooper's 1,000-acre farm south of Dayton.

The Patterson family moved from Lexington to Dayton in the summer of 1804 and named the farm, "Rubicon." The Pattersons also brought their enslaved workers.

The 1803 Ohio Constitution forbid slavery in the state. Some, like William, registered as free blacks on the Montgomery County record of "Black and Mulatto Persons," but continued to work for the Pattersons. Another, Moses, attempted to run away, but was captured by William Lindsay (Elizabeth's brother) and returned to Kentucky, a slave-holding state.

Legal proceedings were filed against Robert on behalf of enslaved workers Edward and Lucy; when Robert lost his case, he set the remaining enslaved workers free. Some of these former enslaved workers chose to continue to work for the Pattersons; little is known about them.

Robert operated a saw mill and grist mill, with area farmers bringing wood and grain to be processed. A large grove of maple trees on the farm was tapped for syrup. Flour, grain, and meat, were sent by wagon and boat to Cincinnati.

As the community grew, the Patterson children attended school in town and the family attended church in the log-cabin First Presbyterian Church (forerunner of today's Westminster Presbyterian Church in Dayton). Robert and Elizabeth contributed financially to building its first brick meeting house. Robert preached on occasion and Elizabeth was active in the Dayton Female Charitable and Bible Society.

The Pattersons were also part of the social fabric, attending dances, dinners, and political meetings in the original courthouse and taverns, and riding, as well as racing.

Eventually, all six of the daughters and one of the surviving three sons were married.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: READ ABOUT THE MARRIAGES AND MILITARY SERVICE OF THE PATTERSON CHILDREN!

With the outbreak of war between Great Britain and the United States, Robert was commissioned a quartermaster for Ohio. He assigned the responsibilities of running the farm and mills to Elizabeth and his sons.

Despite the work of raising a large family and running the family business, Elizabeth maintained her church attendance and joined women across Montgomery County in making clothing for the American soldiers. She led the effort to make shirts by organizing and systematizing the work with local communities.

The women of Montgomery County were able to produce 1,800 shirts within a month. This association of women led to the formation of the Dayton Female Charitable and Bible Society in 1815 in Catherine "Kitty" Patterson Brown's house. Elizabeth was elected its first president.

Following the war, the oldest son, Francis, joined an Ohio militia unit. After his military service, he farmed briefly before moving to Palmyra, Missouri, where he became a merchant.

When the Pattersons first moved to Dayton, they lived in a two-story, log house that Daniel Cooper built. In 1816, Robert and Elizabeth built a brick home in the Federal style. With success in business, they were able to double the size in 1820. Dayton History owns and operates the Patterson Homestead, which is open to the public.

As sons Robert Lindsay and Jefferson took on more responsibility running the farm and mills, Robert focused his attention on connecting Dayton to the rest of the nation. He understood the value of efficiently transporting goods across Ohio to larger markets in the East.

In the early 1820s, Robert's health began declining. The wounds he suffered from the 1776 Native-American attack continued to plague him. Robert died on November 9, 1827, age 74, at the Patterson Homestead. He is buried in Woodland Cemetery.

Following Robert's death, Elizabeth, then age 67, moved into the home of her youngest son, Jefferson, and his wife, Juliana Johnston Patterson, in town. She suffered from rheumatism, but remained active in the church until she caught a bad cold in early August 1833. Following the death of son, Robert Lindsay, on August 13, Elizabeth continued to decline and died on October 22, 1833, age 74. She is buried alongside her husband at Woodland Cemetery.

ENDNOTE - Read a description of the Lindsay home!

"The Lindsay home, a beautiful large mansion with stone columns and broad porches...was surrounded by extensive grazing lands. The Lindsays owned the mills and several thousand acres of forest and meadows and many herds of fine cattle." (Citing John Patterson [Robert's cousin], in Conover, 1902, p. 196).

ENDNOTE - Read about the wedding!

The wedding ceremony was held at noon March 29, 1780, at the Lindsay home, Falling Springs (now Chambersburg), Pennsylvania. Elizabeth was 20, Robert was 27.

John Patterson, Robert's cousin, described the wedding, "The wedding dinner, a rich feast of game and viands [usually refers to beef or steaks] on tables in the grove, was a great feature of the frolic of several days of feasting and merry making." (Conover, 1902, p. 196).

ENDNOTE - Read about Elizabeth's thoughts on the Battle of Blue Licks!

Commenting on the battle, Elizabeth relates, "Myself and the other women, knowing of the atrocities committed by the savages upon captive women, were determined to die in defense of the stockade, rather than surrender. We were on night relief duty all the month [of August] to keep the men on duty awake; other men to sleep unless called in emergency.

Within the Lexington stockade during this trying time, while alarm and excitement were intense, perfect order prevailed, though none could sleep, through dread for the little ones as well as for ourselves. The older women had trained for this, and stationing us all as sentinels at the loop holes, rifles loaded, even half grown girls having places, instructed us for action in emergency. Some had skill as marksmen, others timid, but all standing to their posts, some to load rifles for others to fire.

Through this long night this guard was kept, and the first signals of relief came from wounded men lying in the line of woods outside of rifle range, awaiting break of day, fearing the women in the fort might be further terrorized at suspicions of presence of a treacherous foe. Wives were called to assist their wounded into the fort, and news came to others of the death of husband or son in the blood combat.

The scenes of mourning and distress were heartrending as the bodies of wounded and dead were borne in on litters. I had messages from my husband by these wounded but did not see him until the second day after the battle of the Blue Licks, but had a note from him saying 'I commanded the second line in Todd's battle and am safe, with love to you all. Joseph [Elizabeth's brother] was killed" (Elizabeth L. Patterson quoted by the Reynolds Family of Lexington, Conover, 1902, p. 224).

ENDNOTE - Who were the Patterson children?

The Pattersons had 11 children, 9 of whom lived to adulthood. They were:

* Dayton historian, Charlotte Reeves Conover, in Concerning the Forefathers (1902), suggests that the stress of living under the threat of Native-American attack, newness of being a mother, as well as primitive living conditions, including inadequate nutrition, with respect to Elizabeth, may have played roles in the death of the infant sons (pp. 232). (See also Conover, 1902, pp. 276 — 277)

All of the latter nine Patterson children lived to adulthood. More information about them can be found in the Wright State University Special Collections and Archives.

ENDNOTE - Patterson children marriages & military service

Marriages of the Patterson children:

(Conover, 1902, pp. 276 — 277)

Military service of the Patterson children:

(Citing a letter from Henry Stoddard, Conover, 1902, p. 302)

Conover, C. R. (1902). Concerning the Forefathers: Being a Memoir, with Personal Narrative and Letters of Two Pioneers, Col Robert Patterson and Col John Johnston. New York: Winthrop Press.

Conover, C. R. (1917). The Story of Dayton. Dayton, OH: The Otterbein Press.

Hurt, D. R. (1996). The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720-1830. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Knepper, G. W, (1989). Ohio and its People.. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press.

Do you have photos, books or other information that you believe may be pertinent to this website?

Are you interested in contributing to our organization?